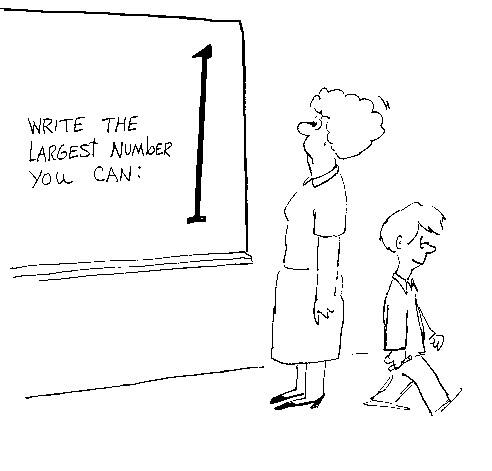

But why would errors in learning matter *so* much? Surely we just tell them the correct answer and they learn that?

We all know it is important that children do not learn incorrect information. I think is is axiomatic that no teacher intends for this to happen but I would ask some teachers, perhaps you, to think about how we 'protect' children from learning the wrong thing.

We all know it is important that children do not learn incorrect information. I think is is axiomatic that no teacher intends for this to happen but I would ask some teachers, perhaps you, to think about how we 'protect' children from learning the wrong thing.

Also children learn a lot of stuff from their peers, but much of this, according to Nuttall, is simply wrong.

I wonder if it is really possible for a teacher to spot these errors? I know you do some assessment, some questioning, some checking but it might be better to adopt teaching techniques that are more likely to minimise the unwanted, incorrect learning.

What prompted me to write this was the Robert Bjork blog stuff from the learning lab.

This piece in particular:

Retrieval-induced forgetting

Memory cues, whether categories, positions in space, scents, or the name of a place, are often linked to many items in memory. For example, the category FRUIT is linked to dozens of exemplars, such as ORANGE, BANANA, MANGO, KIWI, and so on.

When forced to select from memory a single item associated to a cue (e.g., FRUIT: OR____), what happens to other items associated to that general, organizing cue?

Using the retrieval-practice paradigm, we and other researchers have demonstrated that access to those associates is reduced. Retrieval-induced forgetting, or the impaired access to non-retrieved items that share a cue with retrieved items, occurs only when those associates compete during the retrieval attempt (e.g., access to BANANA is reduced because it interferes with retrieval of ORANGE, but MANGO is unaffected because it is too weak of an exemplar to interfere; Anderson, R.A. Bjork, & E. L. Bjork, 1994, Experiment 3).

We argue for retrieval-induced forgetting as an example of goal-directed forgetting because it is thought to be the result of inhibitory processes that help facilitate the retrieval of the target by reducing access to competitors. In this way, retrieval induced forgetting is an adaptive aspect of a functional memory system.

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!

No comments:

Post a Comment