I am somewhat troubled, by many things, but this particular trouble is to do with learning.

Can we see learning? Can we detect learning has happened? Can we identify any link with the teaching activities that happen in classrooms that lead to learning?

It is so obvious that, over time, say a term of school, learning must have happened. Children who attended my physics lessons did have more physics knowledge than they had at the start of the term. They could answer questions on test papers that they previously had no knowledge of. By any definition, learning had happened.

What has caused this learning to happen?

It must be due to something that the learner has done. They must have interacted with the physics I was trying to teach them in some way. It is an active process on their behalf. By active I mean they must have been thinking about the physics, I do not mean they will have been physically active. Only thinking type activity will cause learning. It is the thinking part that has allowed them to connect the physics to stuff already in their brain. That connecting is one part of the process called learning but only when that stuff is retrievable. It will be retrievable during the lesson but learning that is useful for school stuff becomes so when it is retrievable some time after the time when it was first encountered. When it is used to support further learning next term, or in the exam etc.

The next part is for those connections to be made more secure. That is done by practice, lots of questions and problems to be solved. Put the numbers in the equations. That could have been a mechanical task with minimal thinking but for true learning which would lead to understanding the 'just stuffing numbers into the equation' type practice would not lead to any significant depth in understanding. Can-do learning rather than the more valuable does-understand learning.

So, because learning which is evidenced by the degree of understanding the child shows takes time some folk say we cannot evidence learning in a short time period such as a typical lesson. I think I must agree with that. But that does not mean we cannot identify that the early parts of the processes have happened. That the teacher has done his/her job in providing the appropriate conditions for the learning process over time to then have a good chance of happening.

What system would we need to be able to observe that? Seems possible to me. We would be saying something like, 'On what I have observed secured learning is likely to be able to happen in the future.'

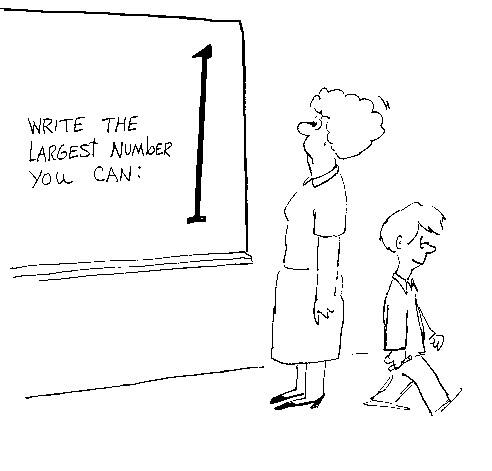

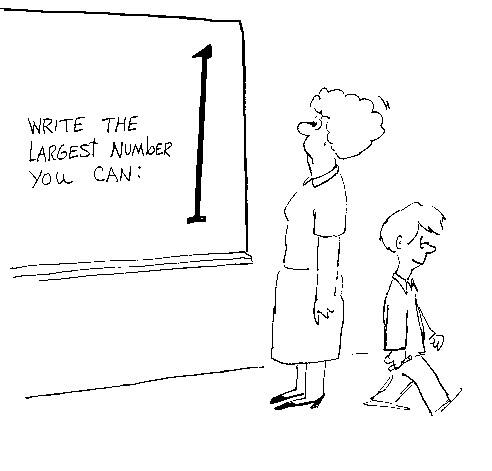

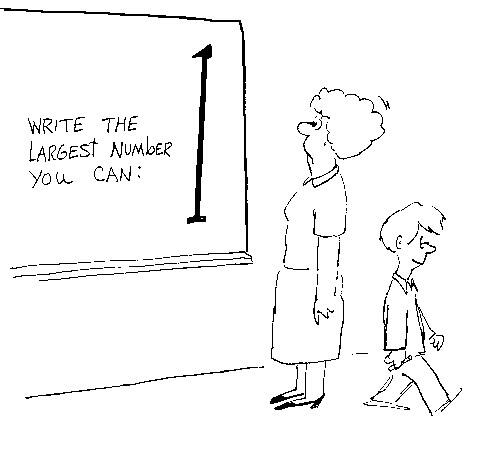

Diagrams are good, pictures work. So here is one to try to describe the learning process I have identified above:

Initial event (teacher explains some physics) --- Child can repeat or use in some simple way this physics content --- child practices and thinks more about the physics --- future lessons same material gets used to support additional learning --- child continues thinking and gains deeper understanding --- more secure knowledge results

Well, it is a sort of a diagram!

In the course of a lesson we can only hope to observe the first three parts of this process and then only of the teacher chooses to do any practising of the newly presented material.

A bit like trying to observe my journey from North Wales to watch Saracens play in the Heineken Cup Final in Cardiff but only watching me prepare and then leave. Not certain that I will get there in time but some factors would show I was possibly going to succeed.

Is that good enough?

ManYana Ltd, Achieving Tomorrow, Today. Education, training and consultancy. http://www.manyanaeducation.co.uk

Monday, 28 April 2014

Monday, 7 April 2014

Correcting Errors in Learning

But why would errors in learning matter *so* much? Surely we just tell them the correct answer and they learn that?

We all know it is important that children do not learn incorrect information. I think is is axiomatic that no teacher intends for this to happen but I would ask some teachers, perhaps you, to think about how we 'protect' children from learning the wrong thing.

We all know it is important that children do not learn incorrect information. I think is is axiomatic that no teacher intends for this to happen but I would ask some teachers, perhaps you, to think about how we 'protect' children from learning the wrong thing.

Also children learn a lot of stuff from their peers, but much of this, according to Nuttall, is simply wrong.

I wonder if it is really possible for a teacher to spot these errors? I know you do some assessment, some questioning, some checking but it might be better to adopt teaching techniques that are more likely to minimise the unwanted, incorrect learning.

What prompted me to write this was the Robert Bjork blog stuff from the learning lab.

This piece in particular:

Retrieval-induced forgetting

Memory cues, whether categories, positions in space, scents, or the name of a place, are often linked to many items in memory. For example, the category FRUIT is linked to dozens of exemplars, such as ORANGE, BANANA, MANGO, KIWI, and so on.

When forced to select from memory a single item associated to a cue (e.g., FRUIT: OR____), what happens to other items associated to that general, organizing cue?

Using the retrieval-practice paradigm, we and other researchers have demonstrated that access to those associates is reduced. Retrieval-induced forgetting, or the impaired access to non-retrieved items that share a cue with retrieved items, occurs only when those associates compete during the retrieval attempt (e.g., access to BANANA is reduced because it interferes with retrieval of ORANGE, but MANGO is unaffected because it is too weak of an exemplar to interfere; Anderson, R.A. Bjork, & E. L. Bjork, 1994, Experiment 3).

We argue for retrieval-induced forgetting as an example of goal-directed forgetting because it is thought to be the result of inhibitory processes that help facilitate the retrieval of the target by reducing access to competitors. In this way, retrieval induced forgetting is an adaptive aspect of a functional memory system.

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!Sunday, 6 April 2014

Modelling learning

Left is the slightly more complex model of working memory I now want to consider. It does not include one important element of the process. That is the sensory data ALL goes into the brain and causes neuron changes. But it is good enough, I think.

Below, a simpler version of working memory, (although it has lots of arrows!)

Any model has limitation and will eventually fall down if pushed to explain some part of the system it is modelling. All models are attempts at simplifying reality. Think of a model train set that runs in my large loft. It models the timetable from Kings Cross to Hatfield almost perfectly. Great model for the timetable function of the real thing. But when a train, on my model, falls off the track I just lift it up and put it back. NO massive response from the emergency services as there would be for a derailed train in the real world. My model train layout does not even try to model this aspect of the railway.

The clever thing is to use the model with just the right amount of complexity/simplicity to be able to model the features then one needs to have to explore the system.

There are several models of working memory and the constraints and opportunities offered by these models critically affects the way we can think about learning. Cognitive load is a critical feature and one which some teachers who have certain beliefs about learning, I will not label them but if you are not using the ideas of working memory explicitly or implicitly to help you decide on how learning can happen efficiently and effectively then you are, I think, ignoring a critical feature of how we learn. I think you will get your own model of learning wrong.

I am indebted to Sue Gerrard for firstly putting up with me on twitter and then spending a little time with me, live, at ResearchEd in Birmingham to explain why the model that Willingham, and I, had been using was more limited and might then have some distortion in our understanding of learning. I now think I understand the model she prefers. A version of the more sophisticated appears above.

You might like to compare this with the simpler model that Willingham and other use. It is the role of attention, for me in my present very novice state of thinking, that is making me rethink working memory and it's role in learning.

The features that are different from the possibly too simplistic Willingham and others model are:

- Information from the environment into the brain is NOT limited by working memory. All the information that we collect, sense, through our senses enters our brain and changes the brain neuron structure. In one sense our brain 'learns' continuously.

- We also sense internal changes in our body continuously and these changes, feelings, reactions also change the brain structure. This all goes on the background.

- Although all our sensory inputs enters our brain is is not, by any means, accessible or retrievable. As teachers we are critically interested in learning that is retrievable.

- Attention is the device that can select particular items from the massive stream of input from our senses.

- It is NOT true that all the sensory input goes through working memory. This is, I think, a critical issue which is not shown by the Willingham model.

- There are different types of memory. I have not got to grips well enough to write about this, yet. But I will.

It is the function of this attention that is making me rethink whether the Willingham model is complex enough to allow us to think about learning (tests type) as teachers. And the different types of memory will also have an impact, though that is just a gut feeling at the moment.

Willingham has a lovely phrase, 'Memory is the residue of thought' which is a great phrase and evidently obvious. But it might be that the phrase needs to have some reference to attention being the trigger that then allows us to think about the sensory input. The things that can trigger that attention can be emotional, other knowledge from long term memory, novelty, threat and probably many more. Willingham's statement is true but is, possibly, a little too reduced. We also need to be clear about how to get a learner's attention to attend to that which we need them to learn.

- How to ensure we do not distract them?

- How do we ensure that their attention does not focus on something which is not important for the learning we want to happen?

I get slightly uneasy at this as I don't want folk to think I am saying that we should design novel, attention grabbing activities for children as these will support their learning. My worry is that some might think I am asking for what Katie Ashford calls 'fireworks' lessons. Where the novelty and excitement is evident but the effect is to distract the learner.

My thoughts are that we need to think a little more about the role of attention in learning, my version of learning, than we have done. I think it has some differences to the thrust of the Willingham quote about thinking causing memories. I don't know what they are but I am minded to be more cautious about using a simpler model as it might hide some needed complexity. Might not, though!

As a note: The word 'learning' seems to be used differently from the way I and some teachers would use it. For me learning is the thing that gets tested when children do an exam, or use to solve problems etc. In the brain world learning seems to be any change to the brain that is as a result of sensory input. I'll try and be clear which version of the word I am using.

There is a choice. My attention is being pulled in two directions. Rugby or more blogging.

Rugby won! More later.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)