How can you be a different and more effective SLT?

Only read this if you want to change, for the better. Only read this if you think you can be better and in being better you and your staff can be more productive and create the quality learning school that you desire. Only read this if you are feeling that the high level of control you are currently exerting is not delivering the outcomes you actually want for all the humans in your school.

My motivations for writing this are twofold. Like Monty Python that may expand to three or fourfold, or more!

The first motivation is my belief that teachers deserve to work in an environment that trusts them to do their very best and that very best will be good enough to deliver a high quality, humane learning environment that anyone will agree is a place they would want to work in, would be challenging in a good way for all and they would want to send their own children to.

The first belief one needs to have is a belief on teachers. They are, almost without exception, a really great bunch of people who dedicate themselves to the betterment of the children they work for. If you are thinking that your staff are not like this then one question I want you to ask yourself is, ‘What are you doing to make them that way?’ They will behave in the ways that work in your school. If they see a head teacher who focuses on admin then that is what they will do, and being teachers they will do that very well. What really do you want your teachers to focus on? If you don’t answer that question with the word ‘learning’ then you need to rethink what education is all about. Call me a name and stop reading. Write me a comment at the end to tell me so. I’ll read it and if it says something I’ll think about it. Convince me I am wrong, if you can.

If you are still with me then I’ll suggest that what is driving you in the wrong direction is the external pressure of Ofsted. Odd really. What Ofsted want is quality learning. Not a pretend version showing some of the features of an outstanding lesson.You need to understand when great learning is likely to be happening and not try to fake it by having some surface impression of learning. Do you think great lessons always need shared learning objectives? Why? Because you think Ofsted wants to see evidence of shared learning objectives? Have you checked the Ofsted documentation to see if that requirement, shared learning objectives, is there? You might be surprised if you do. You will have to come on one of my courses to see why shared learning objectives are potentially dangerous to learning. Let me tell you what two things are needed. One, a teacher who is utterly and completely clear what the learning needs to be and how best to get there. And then, two, school systems that support the kind of classroom environment that allows great learning. (Classroom is shorthand for any learning space.)

The second motivation comes from reading Twitter. I am saddened by the number and nature of the reasons teachers give for feeling highly, far too highly, pressured by their leadership teams. The micromanaging of teachers is a really dominant feature and it is such a stupid and destructive thing to do. Teachers are some of the brightest and most highly motivated workers in this country. Why on Earth do you think they need to be managed like 15 year old trainee chefs? Nothing against chefs by the way.

To use a military metaphor, ask yourself if a general micromanages his/her troops? What would happen if that were the case? That is not what Sandhurst teaches its leaders! Train teachers well. Use your inset time properly and then check the outcomes. You have to trust that your training is effective and not try to catch every raindrop yourself.

Trust appears frequently in my thoughts about teachers. Not a blind, fluffy trust but a hard headed I-have-trained-them-well and they are bright, motivated individuals trust. Hold them responsible for their outcomes and trust that the methods they use, while fitting in the broadest outlines you can construct, are properly thought out. You will be fully aware of the latest and best evidence on learning. No brain gym here! No learning style based teaching in this school. You know the myths and have provided the evidence for their ineffectiveness.

You also know that great teaching does not have to look like the rather blinkered view of what makes a great lesson that you hold yourself. Lessons you like. A great lesson is where the likelihood of great learning exists, time and time again. Exists over lessons throughout the term and is not measured by a single short observation supported by a clipboard and a check list! A great lesson does not have features. It has great learning.

So what was my system for getting the best out of teachers?

First is to go and look at and listen to the learning around the school. Visit lessons but with no agenda other than to see what is really happening. Visit lessons where there is a supply teacher. Visit anywhere there are children supposed to be learning. Of course teachers need to know that you will be touring the school, or your SLT will but they should be certain that you are never looking at individuals. You are trying to pick up the patterns in what happens in your school. I never used a checklist, other than the one in my head that allowed me to be aware of the features of lessons that were likely to lead to better learning. Sometimes I would stay in a lesson for only a few moments. Sometimes I could stay for a good fraction of the lesson. It just depended on what I saw. I was asking the questions; what is going on here and how is it contributing to learning?

I would see traditional lessons, my preferred style, and progressive lessons. Neither got credit or discredit because of the way the lesson was delivered. Did I think there was evidence that this lesson would lead to learning was my criterion. I knew from previous exam data that different teachers got good or less good results with different groups of children. I was not about to impose a way of working that was good for that teacher and that class. I had boundaries, but that is not the issue here.

The data I collected were what was repeatedly seen on my, and other SLT and HoDs and Heads of Year, visits.

We then collated what we had seen and where there were patterns we used those to build our inset programme. We might have been looking to see of the previous insets had been successful. Think carefully about that because the fact that we rarely saw evidence of what the previous inset had focused on could well have meant it was not a useful thing to have been taught about, or perhaps we taught it wrongly or … lots of other possibilities.

We may well have seen student behaviours which we liked or did not like. Put these findings into the inset plan if there was evidence of a pattern.

Quite a simple model, really. I could come to your school and teach you how to do it. I toured the whole school at least 3 times a week. Took me just over an hour for a typical tour.

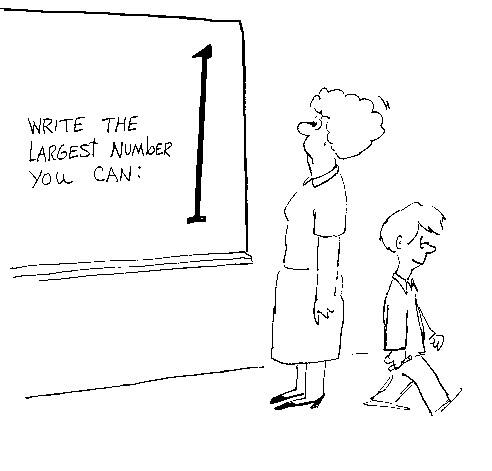

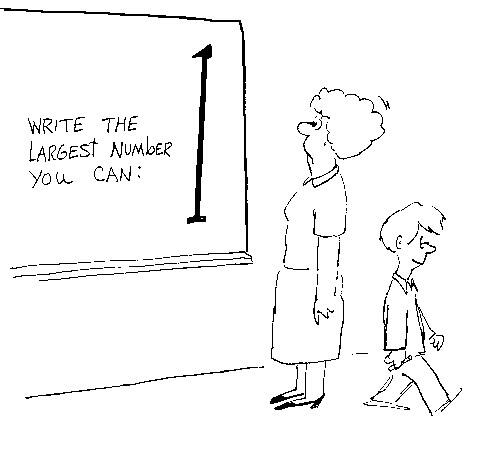

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!

Now, it seems to me that this retrieval induced forgetting might be a rather lengthy process which we would rather avoid. But if you insist on allowing children to explore too much and learn wrong stuff you might need to think about adding lots of time in your future planning to try to encourage retrieval induced forgetting. That is plan how to tell them the right stuff enough times so that they get what they could have got in the first place!